Think Big: Insights from the RBA’s latest gaze into the crystal ball

News

News

Predicting the future is a hard act at the best of times, and especially so during a global pandemic.

Nevertheless, RBA assistant governor Luci Ellis had a crack at it on Friday, in a speech at the Australian Business Economists Lunchtime Briefing.

Ellis’ comments accompanied the central bank’s quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy, which includes its latest set of forecasts on the primary inputs for the Australian economy (GDP, inflation, employment).

Her outlook was based on scenario analysis centred on the base-case forecast outlined by RBA Governor Philip Lowe earlier in the week, with corresponding upside and downside predictions.

She also addressed the key question for investors when it comes to the economic outlook — how long until things get back to normal?

Flagging a “slow and uneven” recover, Ellis said local GDP growth would “probably take several years to return to the trend path expected prior to the virus outbreak”.

Ellis said the bank’s baseline forecast was modelled around COVID-19 trends globally, with large and sudden contractions before activity “begins to recover quite quickly” as infection rates decline.

However, by this stage everyone is well aware of the lingering uncertainty the virus creates. And Ellis said where that showed up most was in consumption — the biggest component of Australia’s GDP at around 60 per cent.

“Probably most importantly, the deficiency in demand and a general increase in uncertainty induces people and firms to be more cautious in their spending decisions. So demand remains weak for some time,” Ellis said.

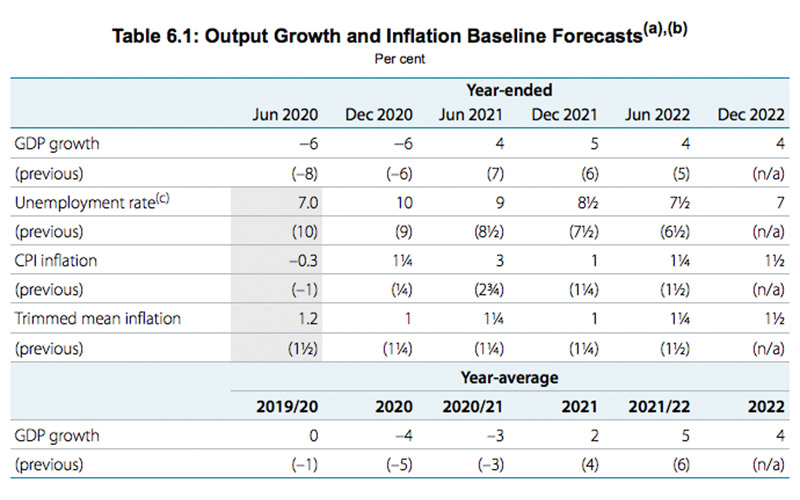

Using its baseline scenario, here are the bank’s latest set of forecasts for the Australian economy:

Of note is the unemployment rate, which the RBA now expects to continue climbing and stay elevated above 10 per cent through to the end of 2020.

While the fall in total hours worked during April and May wasn’t as bad as the bank initially feared, Ellis said pockets of weakness emerged in June and July.

“Payroll data suggest that the recovery in employment began to falter in the second half of June and into July, even before the lockdown in Melbourne came into effect,” Ellis said.

In addition, the RBA’s inflation outlook also remains muted, with CPI growth expected to track below its 2-3 per cent target all the way until the end of 2022.

Via his Twitter account, IFM Investors chief economist Alex Joiner directed readers’ attention to the “trimmed mean” inflation line, which could have a bearing on the RBA’s future policy settings:

And no trimmed mean inflation near the lower bound of the Bank's target, underscoring the likelihood of only more policy stimulus to come rather than less #ausbiz

— Alex Joiner (@IFM_Economist) August 7, 2020

Which way from here?

Factoring in the difficulty of predicting how the crisis will play out, here’s what needs to happen for the situation to either exceed or fall behind the RBA’s baseline forecast:

Upside:

– Infection rates fall more quickly than expected and stay low;

– That gives larger states a catalyst to ease restrictions faster, similar to existing measures in smaller states;

– Households get a confidence boost, and pull the trigger on spending some of that extra cash they’ve saved up during the pandemic.

Downside:

– Infection rates continue to rise globally. More Australian states (not just Victoria) face stricter measures such as stage-four lockdowns;

– Confidence is damaged and GDP growth lags, with the extent of the fall governed by the length of additional lockdown measures.

Assessing how those scenarios interact with pre-existing risks such as US-China tensions, Ellis said the main variable related to Australia’s border shutdown.

For both the baseline and upside scenarios, the RBA’s prediction is that Australia’s international borders remain closed until June 2021 (with specific exceptions such as international students). The downside will see that extended all through the next year.

And there’s also the possibility of medical breakthroughs around vaccines or treatments. However, Ellis highlighted that a vaccine didn’t mean an immediate return to normal activity.

“An effective vaccine would take a bit longer to be distributed, so it would mainly affect outcomes next year and the year after,” Ellis said.

“But it could also result in a stronger recovery than we have assumed even in the upside scenario presented here.”