DroneShield: Demand spikes, revenue jumps 60% as new era of warfare becomes reality

News

News

Aussie-listed drone defence specialist DroneShield just dropped a preliminary business update for the December quarter and it’s certainly been a time of plenty as the new era of warfare technology plays out on Europe’s doorstep.

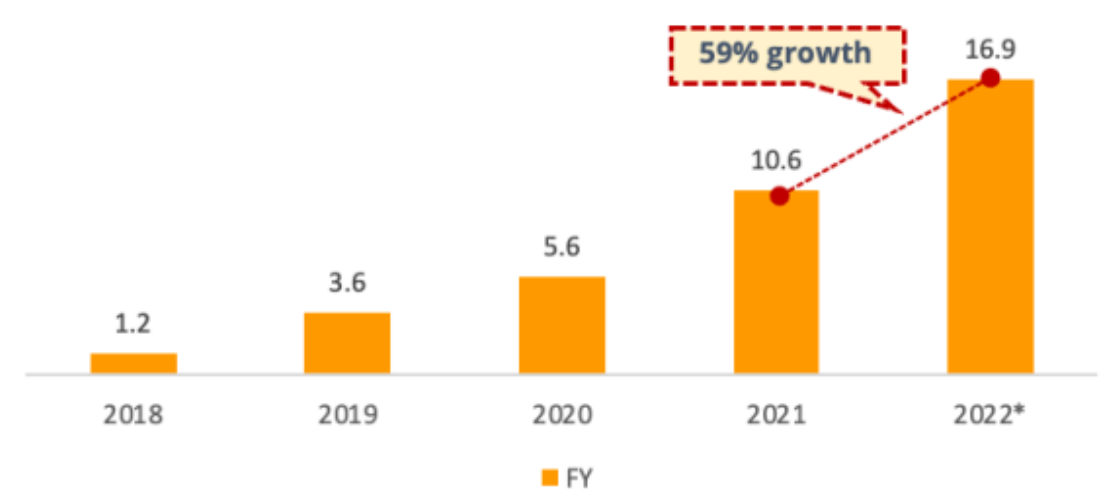

Ahead of DroneShield’s (ASX:DRO) full year in February, the company says revenues for the quarter jumped almost 60% to $16.9 million…

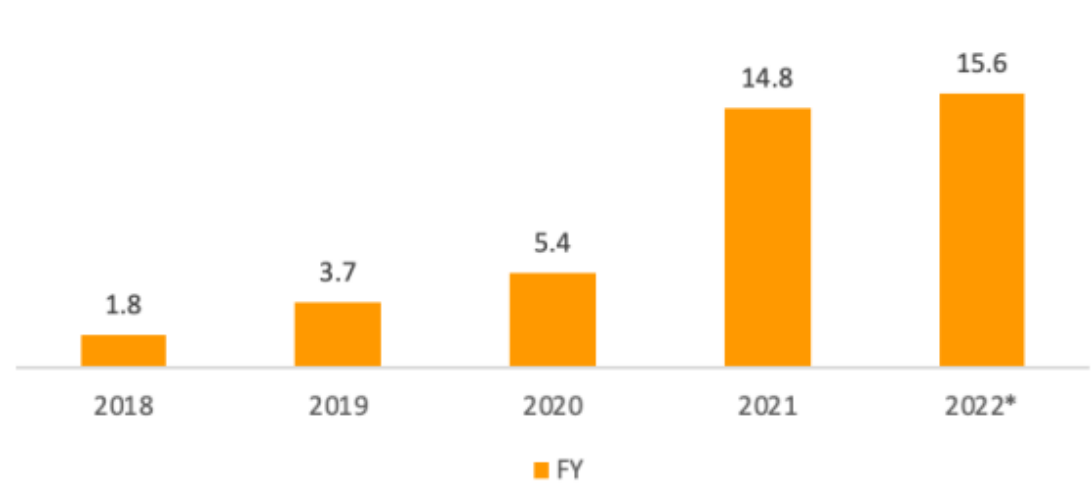

…while cash receipts from sales and grants have risen to $15.6 million.

But while DRO has consistently delivered revenue record years since its listing in 2016, as the war in Ukraine has clearly underscored the critical role the counterdrone industry will play in future conflict and just how rapidly the sector will grow as defence and security budgets rise to the occasion of an increasing uncertainty geopolitical world.

DRO 2022 highlights:

• Record $11 million order (December) followed by another $11 million from a different Gov customer (January), as well as numerous smaller contracts

• $4.7 million in cash receipts for 4Q22, for a total (record) of $15.6 million for calendar 2022

• $10.3 million bank balance as at 31 December 2022. Bank balance as of the date of this report (31 January 2023) was approximately $14.1 million.

• Record order backlog of $19 million in cash receipts as of the date of this report (payments due this year), with $200 million+ in sales pipeline.

• Recommendation by Joint Counter-small Unmanned Aircraft Systems Office (JCO) for a rollout across US Department of Defense (DoD), expected to commence this year.

• Successful completion of $800k Australian DoD Defence Innovation Hub project.

• Successful completion of Canadian military exercise.

• SBIR project awarded by US DoD with partner Quantum Research International.

• $3.7 million investment from Epirus Inc in November, a high-growth US defense technology firm developing software-defined directed energy systems.

• New partnership XRG, for Extended Reality C-UAS training.

• Launch of a dedicated testing facility in Australia.

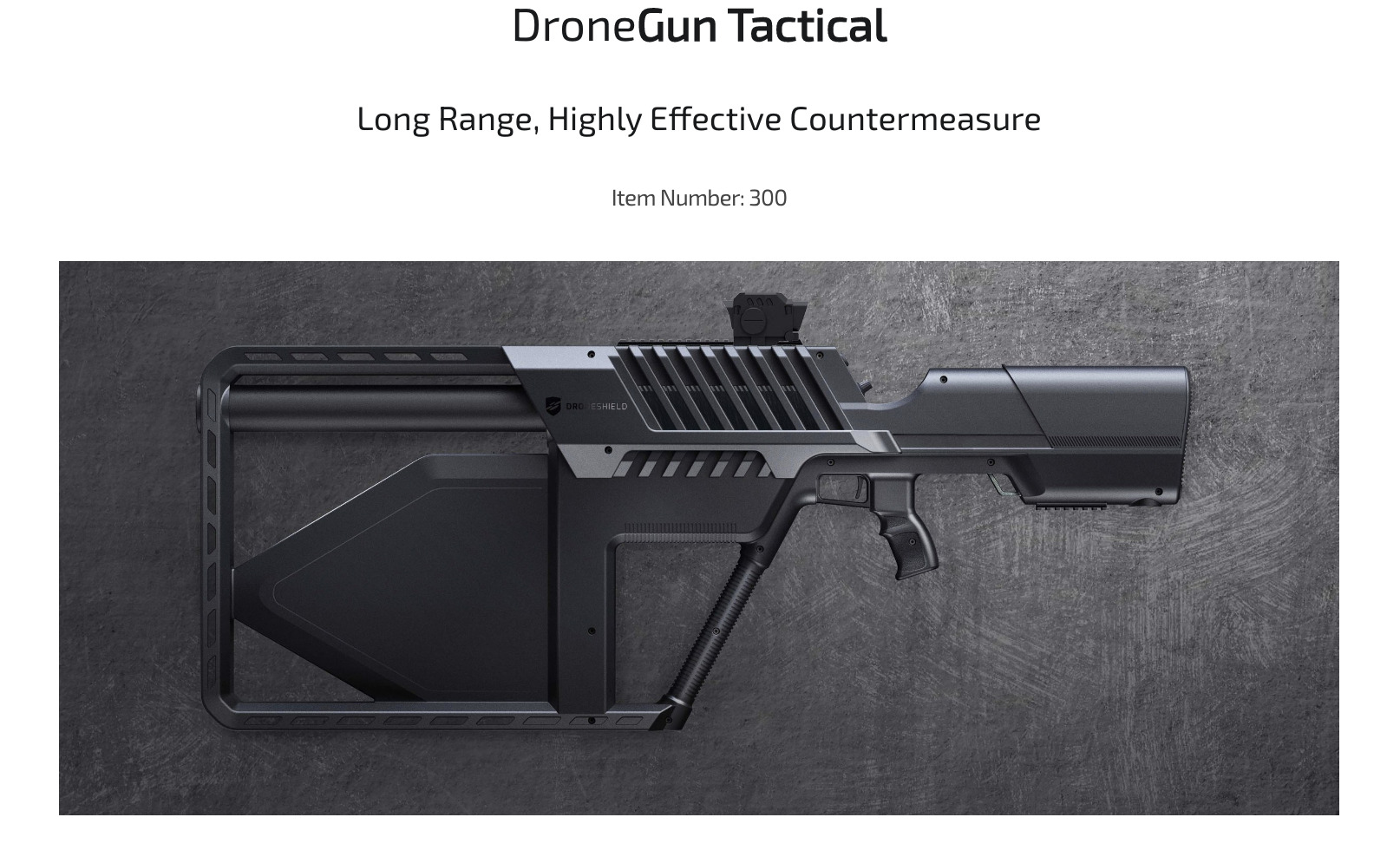

• High-profile DroneGun deployment at Brazil presidential inauguration (held in early January 2023).

• Expanding research coverage by Bell Potter, Peloton and Streetwise Reports.

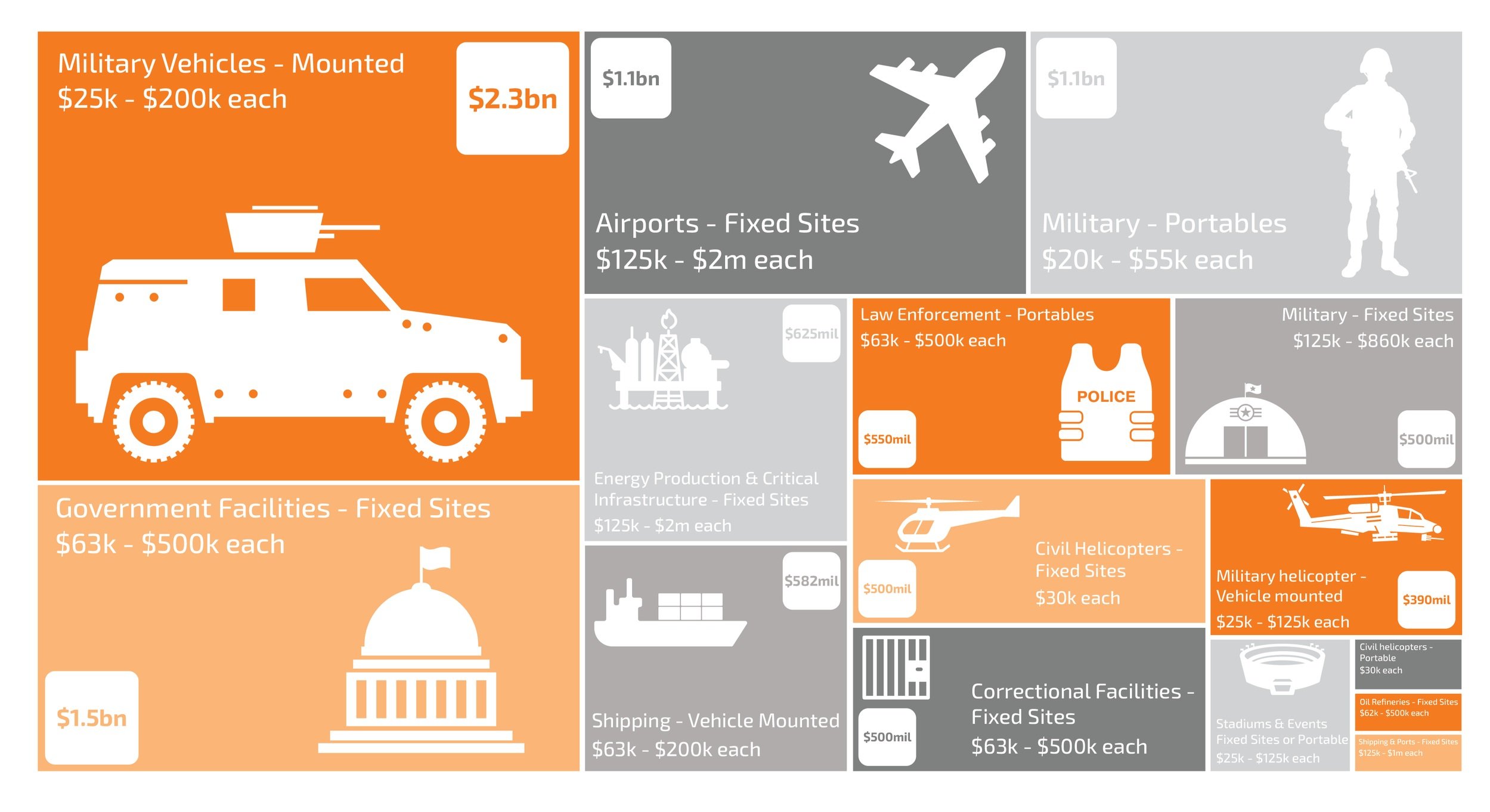

DRO says the counterdrone sector is a potentially US$10bn sector, which simply didn’t exist 10 years ago.

Droneshield chief Oleg Vornik told Stockhead that 2023 will now be “a transformative year” for the business which is now a “proven pioneer and global leader” in the sector.

“(The) Ukrainian conflict (where we have been deployed since the start in February 2022 on the Ukrainian side) has clearly demonstrated the potential of drones and counterdrone systems on the battlefield, coupled with significant non-military use cases for intelligence community, airports, prisons, border security, stadiums, and other facilities.

“Nefarious use of drones is a global and rapidly rising threat, with DroneShield providing proven market leading suite of solutions, directly and also via our network of 100+ in-country partners globally.”

Ukraine – again – was the theatre, but according to Oleg, while the Russian escalation into swarming UAV unmanned aerial vehicle warfare represents a point of no return, the road to weaponised drone-led armageddon has been long and clear and it’s possible we’ve been asleep at the wheel watching it all happen.

“When we set up the business eight years ago, we believed that drone technology was going to rapidly evolve (like any technology), and as such ‘democratise’ the warfare – with drones in war previously limited to only a few countries who could afford to develop and buy larger drones” Vornik said.

Vornik said the first wave of UAS – unmanned aerial systems – and UAV attacks came from ISIS and similar terrorist groups.

“Then the regular militaries learned the lessons, and started to invest in robotic warfare (smaller drones in the air, under water, on the water surface, on the ground, with swarming etc). At this point, drones are everywhere – suicide attacks, dropping charges, directing artillery fire, scoping out battlefield intel etc,” he told Stockhead.

“While they alone do not decide the course of war, they are a part of the combined arms concept, meaning being used in tandem with other parts of the military (such as artillery).”

Back in November, Russia’s Black Sea flagship Admiral Makarov, was – experts say – struck and likely disabled by an incredible Ukrainian drone attack, deep inside Crimea at the impregnable port of Sebastapol.

GeoConfirmed Investigation.

What happened in Sevastopol, Crimea?

A @GeoConfirmed thread.We gathered a lot of footage en we will number our tweets xx/

Thx @TilmanPlan4Risk for this picture.

01/ pic.twitter.com/bJ4A3rcp1P

— GeoConfirmed (@GeoConfirmed) October 29, 2022

Open-source investigators said the frigate was one of three Russian ships to have been hit on Saturday.

A swarm of drones – some flying in the air, others skimming rapidly along the water – struck Russia’s navy at 4.20 am.

(How’s this too!) … it’s footage relayed from one of the sea drones shows the UAV casually dodging enemy vessels:

Very epic footages from today’s attack by drones on the Port in Sevastopol, Crimea

/1 pic.twitter.com/9kDbDBkWPV— Special Kherson Cat 🐈🇺🇦 (@bayraktar_1love) October 29, 2022

Drone and defence expert Derk Wisman, CEO and founder of MSS Defence, says that perhaps no technology with military or “dual-use” application has evolved as quickly than the use of inexpensive drones, illustrated by their game-changing impacts on the battlespace during the Nagorno-Karabakh, Syria and Ukraine conflicts.

“State actors such as Russia, China, and Iran as well as non-state actors and terrorist groups like ISIS have developed and or demonstrated drone capabilities leveraging small UAS for military application. As the advances in drone technology and doctrine continue apace, the need to protect personnel and critical assets with layered and integrated counterdrone systems grow more urgent,” Wisman said late last year.

The Russia-Ukraine war is quickly becoming a textbook case study for the military application of drones.

With all the tragedy, devastation and the high stakes of the conflict, it has also become a testbed for new UAS military technologies.

The drone threat on the battlefield is here and quickly evolving, as currently seen in Ukraine and the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict, and previously across the Middle East.

Wisman says the world is confronting an escalating number of weaponised drone systems “from both near-peer adversaries and asymmetric combatants, boasting increasingly lethal capabilities as technologies advance”.

Oleg says the speed of capability advancement for even modest Commercial-Off-The-Shelf (COTS) drones is sobering.

In 2006 DJI was founded in a dorm room at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

16 years later, COTS drones, like DJI, today provide ISR, contraband delivery, direct attack, and fully autonomous flight against personnel and strategic assets.

Russian Army General Yuri Baluyevsky said in August 2022 that the DJI Mavic’s capability to spot for accurate indirect artillery fire proved “revolutionary” in Ukraine.

Commercial technology advancements will continue to increase the threat level by incorporating swarming, thermal imaging, LiDAR, GPS-denied navigation, and more — with continuing performance enhancements in range (20km range is not unusual today), speed (close to 300kmh recorded) and payload capacity (up to 20-30kg is routine for heavy-lift small drones).

These rapid advancements in COTS and nation-state drone capabilities have fuelled the rise of outfits around the world with counterdrone solutions – like DroneShield – as a must-have aspect in the Electronic Warfare (EW) toolbox.

The ecosystem of counterdrone concepts and capabilities has grown rapidly, mirroring the advancements in drones themselves.

Modern warfare and tactics will continue to evolve. With two recent, full-scale wars, and the current fight in Ukraine, asymmetric warfare tactics are being adopted quickly by conventional forces.

The world’s first full-on drone war has been silently raging in the skies over Ukraine for over a year now.

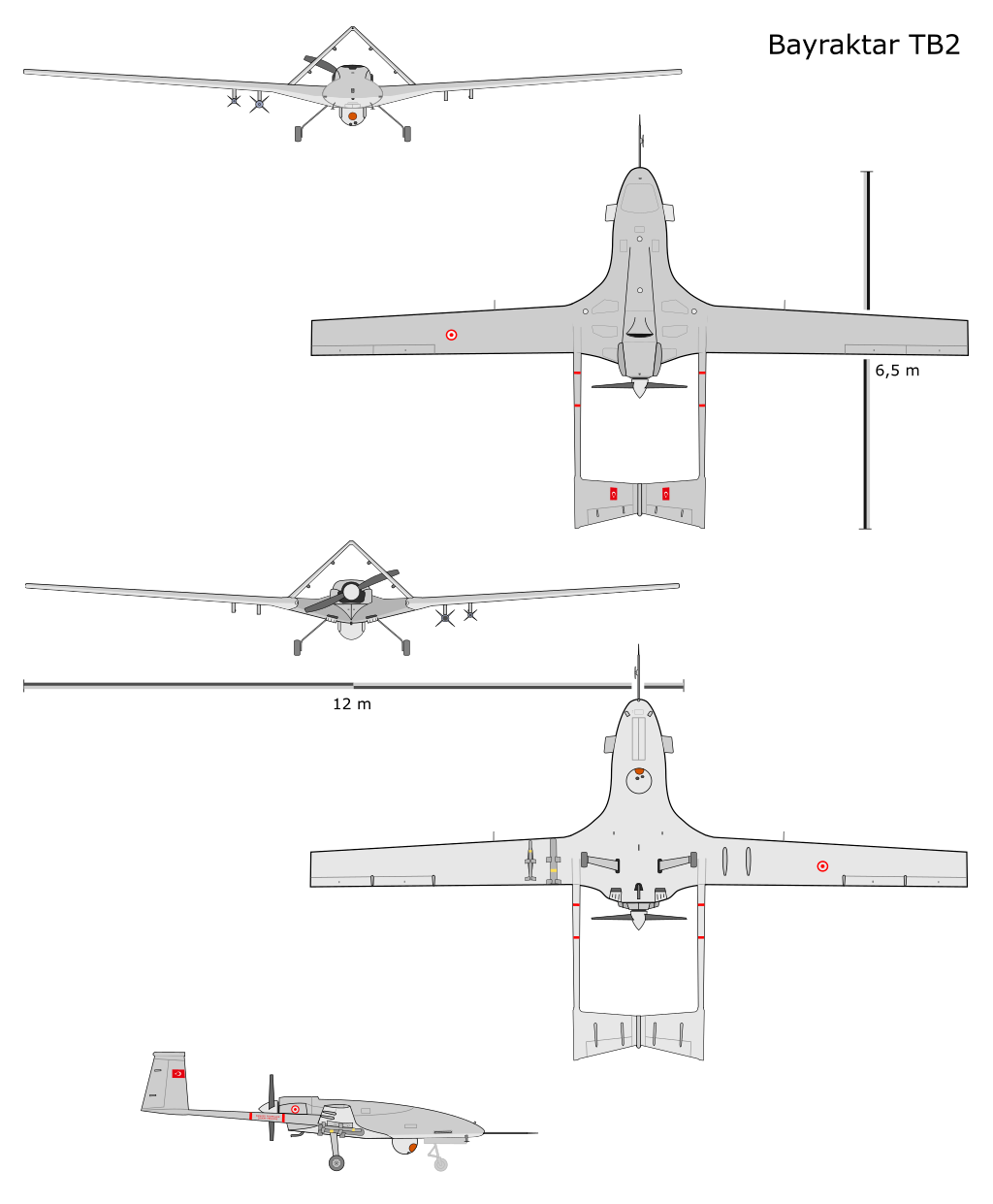

In that time Ukraine has gone from being able to rely on the undeniable superiority of Turkish-made Bayraktar drone, to Moscow moving fast to compensate for its weakness in acquiring the Iranian Shahed (martyr in Persian) drones, used to huge effect in the October civilian targeted bombings across Ukraine.

“These Iranian drones are effectively cheap cruise missiles with a long range and good accuracy. While they are easier to shoot down, they are so cheap that you can use several to overwhelm air defences,” says Jeremy Binnie, Middle East specialist at the legendary defence intelligence firm Janes.

John R. Bryson, Professor of Enterprise and Economic Geography, Birmingham Business School says the war in Ukraine entered a new phase based on ‘the indiscriminate deployment’ of kamikaze drones against civilian targets. Another unhappy first in asymetric warfare.

Prof Bryson is not a fan of the use of Shahed UAV weaponry.

“The use of these drones is like Adolf Hitler’s deployment of the V-1 flying bombs or Vergeltungswaffe 1 (Vengeance Weapon 1) during World War II. The V-1 was deployed as a form of terror bombing of London in 1944. Thus, the deployment by Russia of kamikaze drones represents the use of a new form of vengeance weapon intended to terrorise the Ukrainian people and this is counter to jus in bello (or the right conduct in war).”

Bryson says there’s now an urgent need for the UN to come to some agreement regarding the right conduct in war that tries to ratify in some way the recent innovations in UAV weaponry.

“This must include a clear statement that the indiscriminate use of kamikaze drones targeting civilians and civilian infrastructure is morally unjustifiable and any such use must be defined as a crime against humanity and as a war crime.”

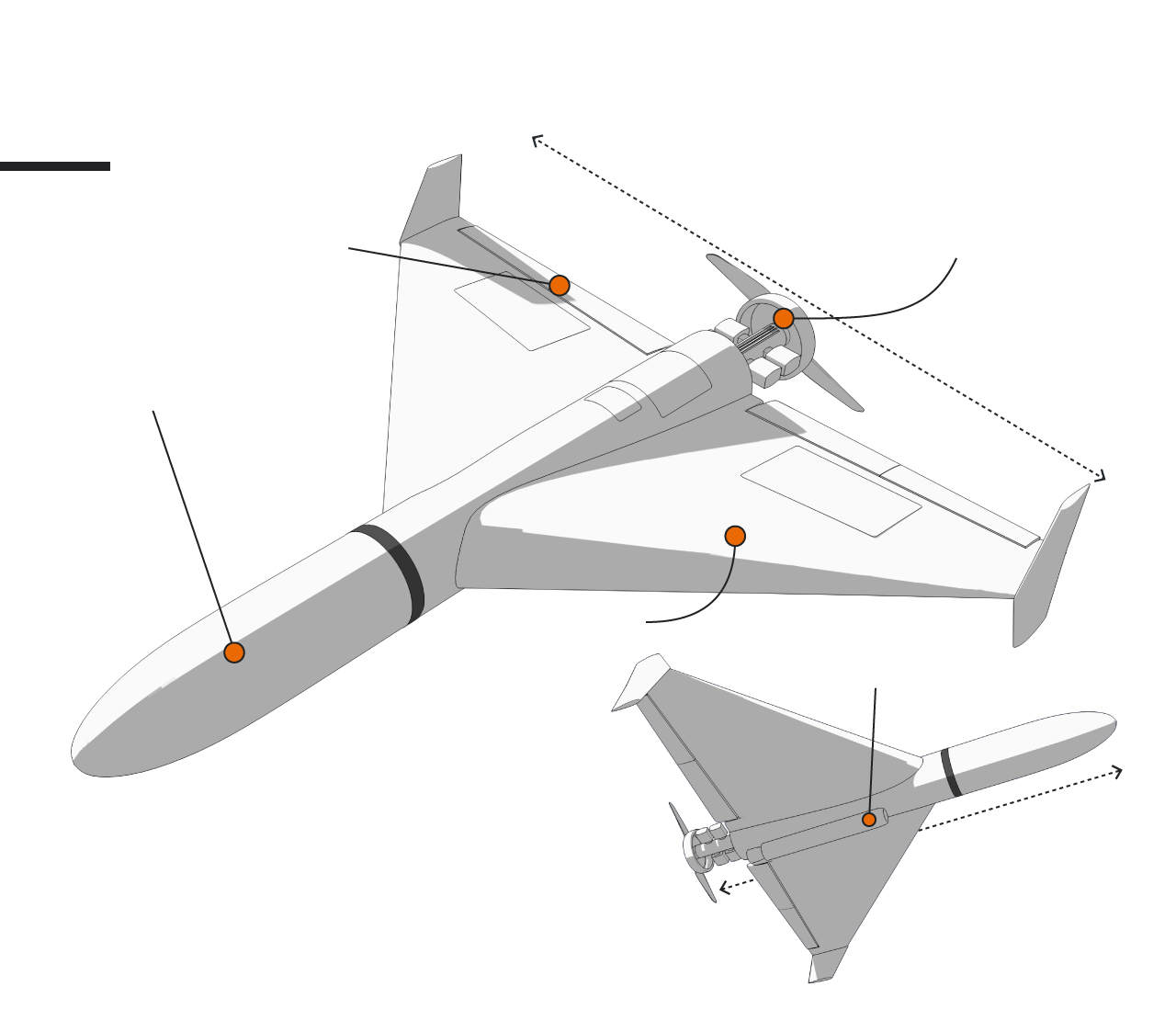

Unlike the Turkish Bayraktar drones, the unmistakable triangular profile of the ‘Shahed’ (‘Martyr’ in Farsi) drones might be pretty basic, but with a 2500km range and a top speed closer to 200km, their purpose (and terror) are in the name.

Shahed-136 drone vector infographic UK Ministry of Defence

Produced by the oft-sanctioned Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industries (HESA) and used in 2019 to spectacular effect against oil facilities in Saudi Arabia, and again this January against the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – it’s easy to see why Iran has dubbed them “martyrs”, a term so loaded that Russia has rebranded with winglet markings as the Geran-2 (Geranium-2 in Russian).

On September 13, the Ukrainian army claimed to have shot down a Shahed-136 north of the Donbas.

Oon September 25, those drones were used against an administrative building in the Port of Odessa, and a week later, a strike was carried out in the Kyiv Oblast.

Writing in Le Monde, Professor Jean-Pierre Filiu said the Shahed-136s are most obviously intended for in-depth strikes.

“Indeed, Ukrainian leaders denounced Russia’s transfer of the drones to Belarusian territory in order to better target Kyiv and northeast Ukraine,” Prof Filiu said.

“These Iranian drones, launched from Belarus or Crimea, were at the heart of Russia’s campaign of terror carried out on October 10 and 11 against civilian targets throughout Ukraine.”

However Newsweek reports this week, that Russian forces could be already running through their stockpile of both Shahed-131 and Shahed-136 drones, that’s according to the Institute for the Study of War (ISW).

Vladimir Putin’s forces have stepped up the frequency of the UAV, or unmanned aerial vehicle, attacks across Ukraine since December, the think tank said in an updated analysis on January 7.

Oleg Vornik says the Iranian drone tech may even have been first sighted in the Ukraine theatre as early as August, but this week’s unprecedented wave upon wave of swarm attacks, in which office blocks tumble and civilians die, is most definitely new.

Swarm strikes on civilian centres in Europe is new to this war, new to Western and Allied war and the success the cheap and accessible systems have had will ensure swarming UAV attacks and other forms of drone tech will make it a likely option of all the new wars to come.

“I think there’s a number of thresholds crossed these last months. Not least the first Western country attacked using drone warfare,” he said. “We’ve seen similar (but less reported) situations in Middle East (Houthi drone attacks on Saudi, including on Riyadh itself; Syria, Armenia/Azerbaijan…”

Iranian-made drones have been used elsewhere in Ukraine in recent months against urban centres and infrastructure, including power stations. More than half of Ukraine is in a winter blackout.

And at the relative steal at circa $20,000 a pop, the Shahed is a revolution in the cheap urban war stakes. And that’s what scares Allied officials. Compared to the cost of cutting-edge missiles, precision strike weaponry, conventional aircraft, the pilots to fly them… why bother with any of that when killing and terrorizing civilians actually is your goal?

The Kalibr cruise missile that Russia has used widely in Ukraine costs the military about $1 million each and Putin is running low.

Drone swarms also make life hell for Ukraine’s current air defences because the drones can be fired in groups of five in rapid succession.

The fleet approach of a Shahed strike can overwhelm both air-defence shields and reliability issues – swarms compensate for (just two-stroke) engine failure or malfunction and even sophisticated shields can’t nullify groups of kamikaze drones infiltrating air-space ‘en masse’.

That’s what DroneShield was created for, Vornik says.

His nightmare drone warfare scenario – multiple drones delivering nuclear, chemical or biological agent, across a busy city.

“Like with everything to do with warfare, ethics is tricky. The objective is to stop the bad guy, with minimal losses of human lives. Drones do allow forward missions that don’t put their human operators in harm’s way. But then of course the bad guys use them to attack civilian targets …”

Oleg says that drones, like any other weapon technology, can be stopped.

“However conventional technologies designed for other purposes (like anti-aircraft artillery) are poorly designed for the task. Drones also come in wide size varieties – from group 1 (that fit into palm of your hand) to full aircraft size – and the approach to detect and defeat them varies across drone size groups.”

Vornik says one system cannot provide a complete fix, and the answer is in an effective “system of systems” for different types of drone threats.

“DroneShield provides optimal detect and defeat systems for defence against smaller drones.”

“Effective defence involves being prepared – system procurement, deployment and training can be done in rapid manner, but still takes time and effort. There needs to be recognition that drone and anti-drone are two sides of same coin, and just as militaries are stepping up efforts to add drones to their defence fleet, so should be counterdrone systems.

“With the Ukraine war, as much of a tragedy as it is, it’s also a wake-up call to our militaries as to what the battlefield of tomorrow looks like, so we don’t train to ‘fight the last war’, but instead anticipate what we may face in future conflicts.”