You might be interested in

Health & Biotech

ScoPo's (actually still Iain's) Powerplays: ASX health sector falls, but several stocks on upward run

Mining

Monsters of Rock: Some of these booming lithium exploration stocks are creeping up on us

Mining

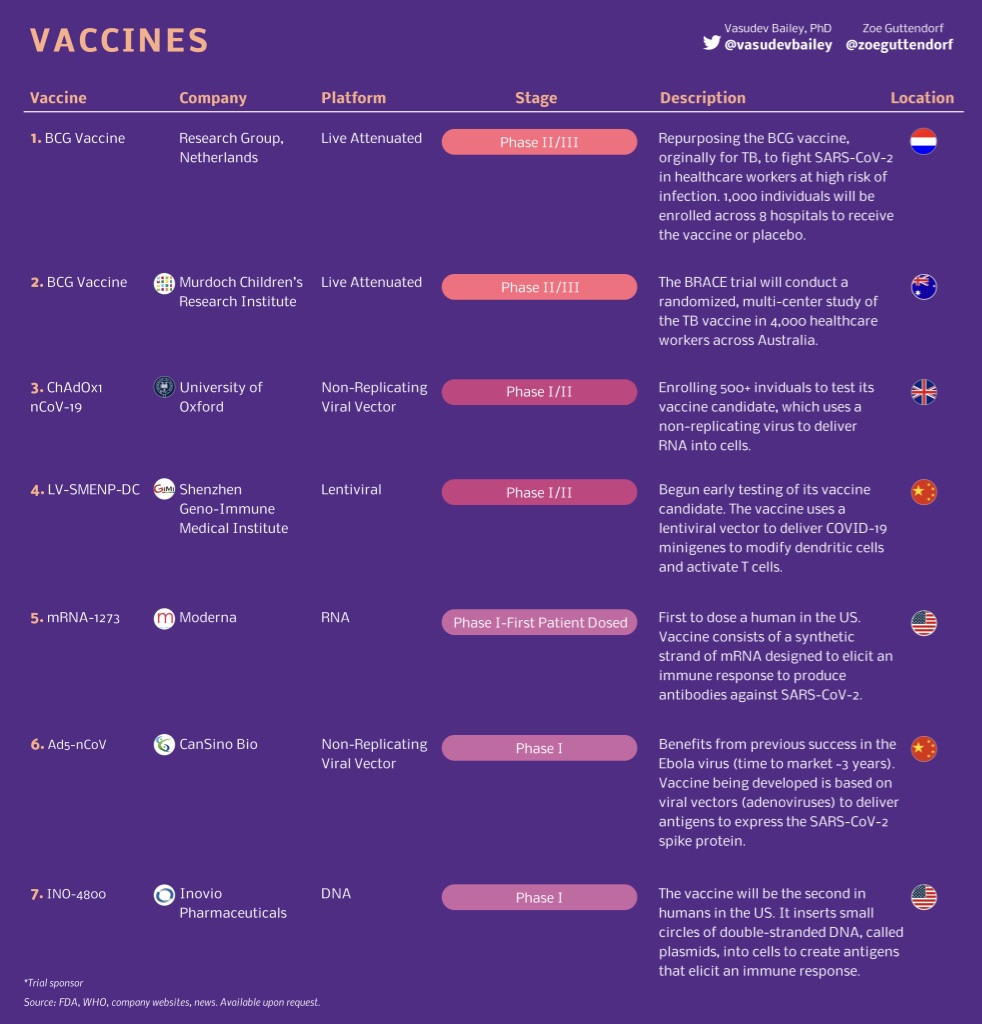

There were 67 COVID-19 vaccines in development around the world as of last week, with two frontrunners close to moving into phase 2/3 clinical trials.

But the question on everyone’s lips, from politicians to those at home waiting to be allowed out, is how long will this take?

At its earliest a vaccine might be available for all Australians by April 2022, based on timelines given by vaccine development and manufacturing experts.

A usual timeframe for a vaccine to be made is two to five years, but rapid development platforms like the one created by the University of Queensland, combined with fast-tracked regulatory approvals, means, science permitting, a vaccine could be available within 12-18 months.

“While the speed with which vaccine candidates have been produced is unprecedented, any likely stumbles will happen in clinical or human trials,” Morgans senior analyst Derek Jellinek said last week.

“Trials essentially screen out the ‘duds’, those candidates that are either unsafe or ineffective or both, which is why clinical trials can’t be skipped or hurried. However, approval can be accelerated, especially if regulators have approved similar products before.

“But we note, Sars-CoV-2 is a novel pathogen in humans and many of the technologies being used to build vaccines are relatively untested too. So we wouldn’t expect any vaccine to be commercialised inside 12 months.”

Once a vaccine is approved there are almost 8 billion people around the world who want it.

Ramping up supply for Australia’s 23 million people would take at least 12 months, meaning it’s not a near-term solution, the Grattan Institute’s Stephen Duckett said during a webinar on Thursday.

Jellinek adds that politics will also likely play a factor into who gets how much, first.

Which means the earliest a vaccine could be finished will be April 2021, and for the non-essential workers among us, available by April 2022.

COVID-19, or Sars-CoV-2 as it is officially known, is a piece of ribonucleic acid (RNA) inside a protein sphere covered in spikes. The spikes connect to receptors on cells in the human lung and allow the virus to break in and start using the cell’s own structure to make copies of itself.

A vaccine arms the immune system by exposing it to a pathogen, in this case the COVID-19 virus, which creates antibodies (the proteins European countries are targeting to create ‘immunity passports’) that can be quickly mobilised against the virus in future.

There are a range of different approaches to building a vaccine, as Stockhead covered in early March, and there are a number of entities trying to speed the process up.

CSIRO’S professor Trevor Drew says the research organisation has been commissioned to develop a system so that anyone with a candidate vaccine (a vaccine that they think will work but hasn’t yet had proof of efficacy) can just plug it into their system and make the process of testing faster.

“It is quite a challenge for us to get this set up, but we hope we’ll have something ready for vaccine producers to use by March or April this year,” he says.

There were 61 vaccines in preclinical development as of last week. They have a 0.007 per cent chance of emerging from the petri dish and into the market.

This means they’re still in the lab; testing is undertaken on animals to find dose levels and whether it might work at all.

Three were in phase-one safety trials. These use healthy humans to work out whether a vaccine is safe.

The most promising candidate is from US-based Moderna Therapeutics, which skipped animal testing and and went straight into a three-month phase-one human trial in April. Fellow American Inovio Pharmaceuticals plans to launch its COVID-19 phase-one trial this month, which has a proposed end date of November.

Chinese company CanSino Biologics has a vaccine it started a trial for in March, with a proposed end date of December.

Phase two tests a small group of people to find out if a drug works. In normal drugs you’d use sick patients, with a vaccine you need to use a healthy person to see if antibodies are produced.

Two vaccines are in phase 1/2 trials, meaning they’re being tested for safety and efficacy at the same time.

University of Oxford is planning to recruit 510 people for a six month study that has a completion date, including post-trial checkups, in May next year. And a Chinese study out of Shenzhen Geno-Immune Medical Institute will inject 100 participants and follow them every three months from April until July 2023.

The final phase before registration and putting a drug (or vaccine) into the market is phase three. This stage is to confirm its effectiveness in a larger, more diverse group of people than in phase two to ensure that previous success wasn’t the product of selective patient recruiting or good lab management.

Both vaccines that are at phase three are fast tracked studies into the tuberculosis vaccine BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin), which studies have shown has an ability to induce potent protection against other infectious diseases.

The Murdoch Children’s Research Institute started vaccinating 4170 healthcare workers with the BCG vaccine in March and expects the trial to run until October, while a similarly time framed study by the Netherlands’ Radboudumc and UMC Utrecht is vaccinating 1500 healthcare workers.