The White House: A Year of Buying Dangerously

Experts

In this series, global equities portfolio manager James White from Lessep IM, ditches micro and macro and embraces “The Meta” perspective.

Lessep IM runs a core portfolio of 40-50 stocks that capture the opportunities in productivity trends and reflect investments in both the drivers of productivity and the beneficiaries of productivity. James also aims to run a long-tail of stocks that have the potential to capture a greater share of new or existing markets.

Inflation has peaked, supply chains are getting back to normal, and there’s no such thing as stagflation in a 2022 economy… just deflation which will be just as bad for low income households.

With inflation the key driver of asset prices at the moment, it’s worth outlining some thoughts on the situation, particularly as it pertains to the United States of Amazing.

In the short-term, headline inflation has likely peaked. In the medium-term it’s worth considering two persistent inflation themes that are of concern to policy-makers, investors, and the general public.

Supply chains will not return to normal.

Stagflation will be the predominant trend in the global economy over the next decade.

Inflation is likely to come down, over the next six months, simply because the pace of monthly price increases has peaked.

Even with historically fast price growth (4% annual rate), annual inflation will fall through the remainder of 2022. Based on price increases in the first half of 2022, year-end annual change in US inflation will be 4%-5%. This compares to 8.5% for the year to July 2022 and below the 7.1% in 2021.

The Choose-Your-Own-Adventure analysis in the chart above highlights the range of outcomes that might be possible for both markets and the Federal Reserve over the coming 12 months. Interestingly, even with no further price increases, it would not be until May that headline inflation finished below the Fed’s 2% target.

But a more aggressive decline in prices may be possible based on an assessment of both supply and demand factors.

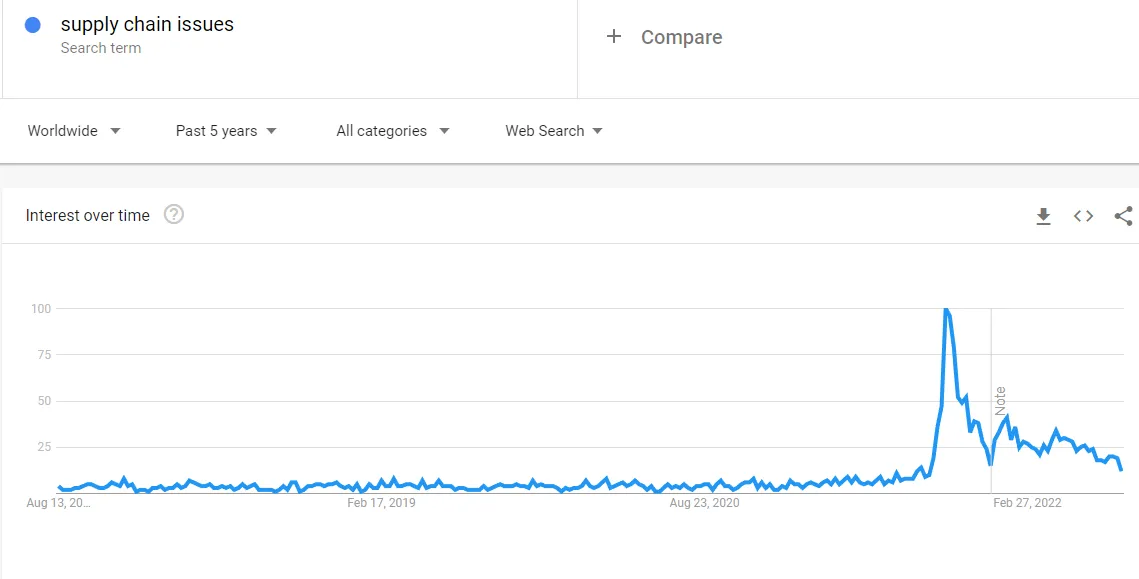

A common theme through this inflationary period has been supply chain issues. Interestingly, it was only in October 2021, according to Google, that supply chain issues entered the public debate. This coincided with the challenges unloading container ships on the West Coast of the United States.

But, according to the LA Times:

Here’s a not-so-scientific tally of where things stand in the Fed’s recent observations: the number of times the word “shortage” appears in the Fed survey, called the Beige Book. These could be references to shortages of labor, materials or other keys to production. Although the number is still more than double its pre-pandemic level, it has declined to about one-third of its peak in August 2021.

It shouldn’t, however, seem bizarre or supernatural that supply chains normalise. In 2019, the world was living in relative abundance. Inflation averaged 1.8%.

The pandemic, generally, didn’t destroy the capacity to produce abundance, it destroyed the co-ordination required to share it efficiently. As co-ordination improves, the abundance of 2019 should be expected to return.

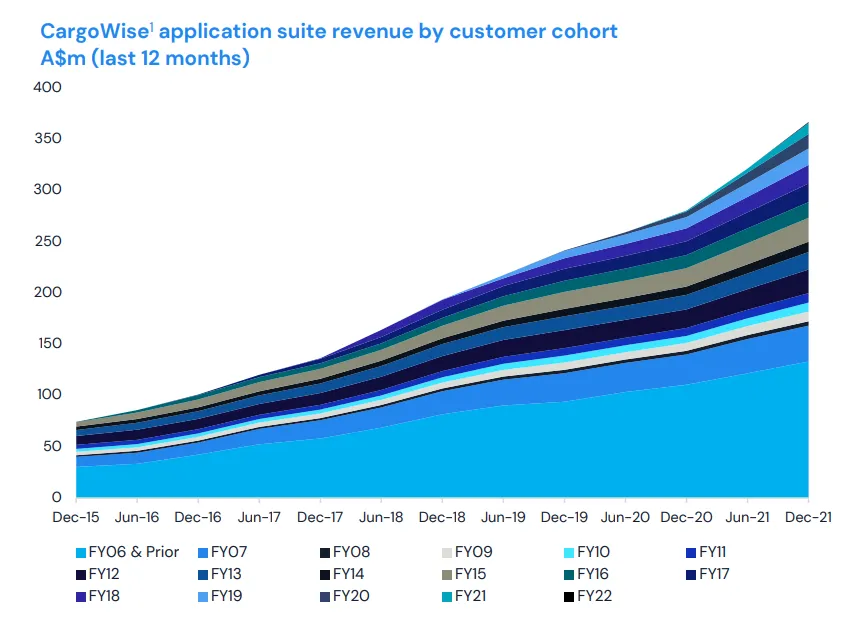

Indeed, the experience of Australian port logistics software company Wisetech highlights that the pandemic may drive further efficiency gains in co-ordination.

Wisetech has seen an acceleration in revenue growth in 2021 and 2022.

In calendar year 2021, Wisetech on-boarded the greatest number of large contracts in its history. To date, however, these customers are yet to aggressively spend. Revenue from these clients will accelerate as the software solutions are implemented.

Wisetech services the freight-forwarding industry.

The freight-forwarders earned more in the last two years than they did in the previous fifty years, as the cost of a container movement increased ten-fold.

The combination of the pandemic, its restrictions, and this extraordinary profit, enabled the industry to invest in automation. Prior to the pandemic, automation was an expensive nice-to-have. In the pandemic it was an easy productivity gain.

As the freight forwarding industry exits the pandemic, it will exit more productively, with less staff, and, most importantly, considerably lower error rates, the costliest part of being a freight forwarder.

It’s likely that across the entire global supply chain, application of track and trace automation, and other innovation and investment, will lead to a more efficient system in the years to come. Prices can return to their long-term trend growth rate.

A persistent concern from investors has been stagflation. Bridgewater Associates outlined its broad market views of inflation and the coming investment environment in an Op-Ed published in the Financial Times. The Op-Ed opened with a discussion of the likely market environment for the next 10 years:

It’s been awhile since investors faced a stagflationary environment and there are good odds that this is what they will face over the coming decade.

In stagflation, a high level of nominal spending growth cannot be met by the quantity of goods produced, resulting in above-target inflation. Policymakers are not able to simultaneously achieve their inflation and growth targets, forcing them to choose between the two.

The likelihood that stagflation will persist, however, even in the next 12 months, would seem low.

From the Lessep perspective, stagflation is a function of two outcomes: an exogenous supply shock, and sticky demand. The 1970s were characterised by an oil crisis, where supply was controlled by the Middle East, and a high reliance on energy to run the economy. It was an economy designed for $3.50 oil, not $10, or $40, as it was in 1980. Consequently, prices rose, and activity slowed as households failed to avoid higher prices for everything.

Today, there is greater room for households to avoid higher prices.

This is not a good thing.

The corollary of a persistent exogenous price shock in the economy of 2022 will be deflation, rather than stagflation. Households, particularly those on lower incomes, will cut spending on non-essential services.

This will slow economic activity, and lead to lower wage growth.

It will, however, lower price growth and enable central banks to ease the pace of monetary policy tightening, and support asset prices.

The outlook for peaking inflation will support the market as asset prices rise.

The greater part of the freight recovery balances on China’s dedication to both COVID-zero and maintaining strong factory and ports activity. That looked all looked pretty good after recent National Bureau of Statistics June data which was China’s second-best month for exports in at least three decades.

And in the meanwhile, greater efficiencies, instituted as a consequence of the pandemic, will lead to greater productivity. But there will be costs for low income households as a result of higher commodity prices.

The views, information, or opinions expressed in the interview in this article are solely those of the writer and do not represent the views of Stockhead.

Stockhead has not provided, endorsed or otherwise assumed responsibility for any financial product advice contained in this article.