Expert view: why the lithium bubble is far from bursting

Mining

Mining

Lithium stocks haven’t had a good run this year, with a large chunk losing steam since the start of the year.

But investors needn’t worry says Marcel Goldenberg – a battery metals specialist for S&P Global Platts.

We spoke with Mr Goldenberg about why there’s still plenty of upside in the lithium story.

What’s your view on the battery metals hype – has it been overdone or is there still upside?

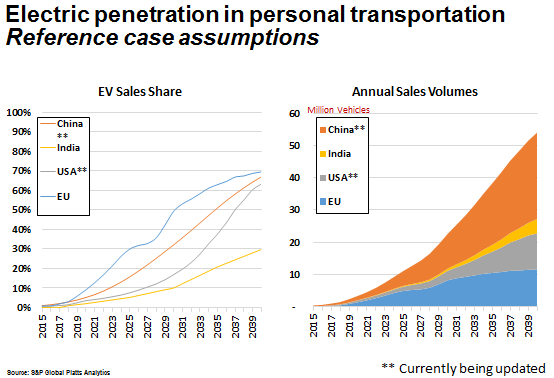

Platts Analytics research shows that by 2025 in the European Union we’ll have about 30 per cent EV [electric vehicle] penetration, China 15 per cent and the US 8 per cent.

That compares to 1 to 3 per cent as of 2018. So we are talking about a 15-to-30-fold increase in the EU and a 10-to-15-fold increase in China.

So have battery metals been over-hyped? No. I’ve been speaking to many people in Australia and often here that every forecast that was done a year or two ago was actually too prudent to where we are now in terms of raw material demand.

Will we over-achieve expectations every year? Probably not. However we certainly are at the beginning of this revolution and not halfway through. I think that’s the one thing that’s really important to note.

We need to remember there are not many electric vehicles out there yet. Electric vehicles are the driver. That’s where the disruption is coming from and that’s where you will see raw material demand coming from and that’s where we are only at the very beginning still.

There are mixed views on the lithium market, and stocks have lost ground over concerns of a looming oversupply. What is your outlook for the market in terms of supply and demand?

I think the one thing we need to focus on when we talk about lithium is how it gets converted.

You’ve got the spodumene here in Australia in particular and the lithium brines mainly in Southern America in your ABC countries – Argentina, Bolivia and Chile – and the spodumene and brine needs to be upgraded from raw material into either lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide and that’s where you start to see the bottleneck.

(Lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide are used to make cathode material for lithium-ion batteries. Lithium hydroxide is becoming more popular among electric car battery makers because it can produce cathode material more efficiently.)

There’s generally a widespread understanding in the market that we have enough lithium to supply the demand that is to come.

But the true bottleneck that one needs to focus on is the conversion capacity from lithium spodumene and brine to lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate, because that currently isn’t going there in three to five years.

What impact will China’s shift to subsidise longer range EVs and not short-range EVs have on battery metals demand?

Before this year it was a per-EV subsidy. China has now adjusted this to focus more on long-range EVs. So if you purchase a long-range vehicle that can, for example, do 400km, you will have a higher proportion subsidised than if you bought the same vehicle last year.

Whereas if you purchased a 150-200km electric vehicle today you would get a smaller subsidy than you would have in 2017.

China is currently the frontrunner on that, most other countries in the world still have per-EV subsidies.

A short-range vehicle however is cheaper than a long-range vehicle, so people looking to buy a cheaper a car may now consider a petrol car more seriously again than last year.

Yet, spinning it back towards lithium demand and battery demand, of course for a producer that’s good news because long-range EVs need larger batteries, and larger batteries mean greater raw material demand.

So it’s a two-sided story. To one extent you are favouring your “better off” customer, but on the other hand you are actually doing well for the producers because it means they need more raw material in the electric vehicle.

There has been a big push by battery and EV makers to cut or even completely remove cobalt from their products. Again there has been mixed views on whether this is possible. What do you see happening there?

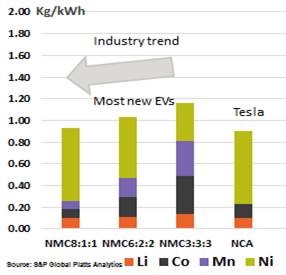

Currently most EVs use the NMC622 battery technology, which stands for six parts of nickel to one part each of manganese and cobalt, but there’s this drive towards the NMC811 battery technology.

The reason behind this is driven by several factors. On the one hand cobalt is very expensive, you’re looking at around $US60,000 for a metric tonne of cobalt compared to the Platts Battery Grade Lithium Carbonate assessment at $US14,500, and nickel is even cheaper than that at the moment.

So cobalt is the most expensive material in the battery. Further, there’s a sourcing issue. It’s a well-known fact that cobalt gets mainly mined from the Democratic Republic of Congo and there are questions and concerns about child labour and general working conditions.

Having said all of that, the EV revolution is only starting and demand for batteries will continue to increase exponentially over the years to come.

So obviously as we move forward, as we have more electric vehicles we need more batteries, and as such the demand for cobalt will increase more and more.

In terms of the market discussions I’m having, market participants state that we will remain short of cobalt for a long time because there isn’t an alternative to it yet.

The NMC811 isn’t commercially viable yet. It’s a technology that we’re looking to be commercially viable maybe in the next three to five years.

So while we’re doing R&D in that space we’re certainly in need of cobalt. And while this research and commercialisation is being done, demand for EVs and raw materials continues to increase.

Marcel Goldenberg is a market and methodology development specialist on the metals side for S&P Global Platts.

He is a metals pricing analyst focusing on benchmark protection and development for Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

This article does not constitute financial product advice. You should consider obtaining independent advice before making any financial decisions.