We need nuclear power to reach our climate goals, but its future remains uncertain

Energy

Energy

There’s been groundswell of support for nuclear energy as an important climate change mitigation technology.

Today there are about 450 nuclear power reactors operating in 31 countries, with a combined capacity of about 400GW.

But nuclear – the world’s second largest low-carbon power source — faces an uncertain future.

It comes down to basic economics. An extended period of low wholesale electricity prices in many advanced economies has sharply reduced or eliminated profit margins.

This is putting ageing nuclear plants — many constructed in the 70s and 80s — at risk of shutting down early.

In the US, which is the world’s largest producer, several plants have retired early and many more are at risk.

Investment in new nuclear projects in advanced economies is even tougher; projects in Finland, France and the US are not yet in service and have been plagued by major cost overruns.

Because of the sheer scale of the investment required, all but 7 of the 54 nuclear power plants under construction globally are owned by state-owned companies. Most are in so-called developing economies.

But a sharp decline in nuclear power capacity would have huge consequences, according to a new report by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Without additional lifetime extensions and new builds, achieving key sustainable energy goals, including international climate targets, would become “more difficult and expensive”.

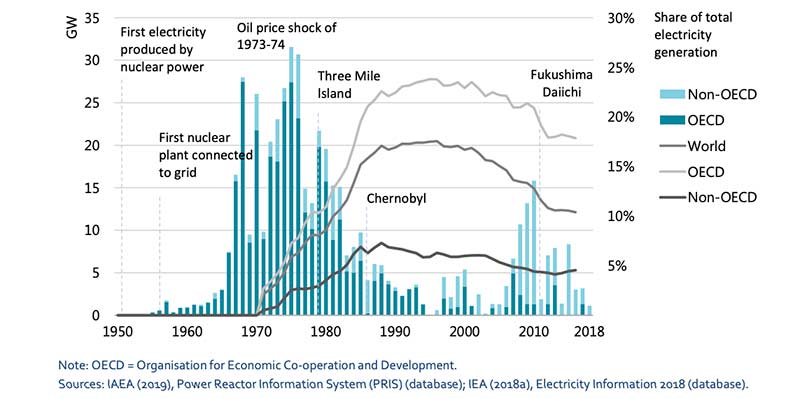

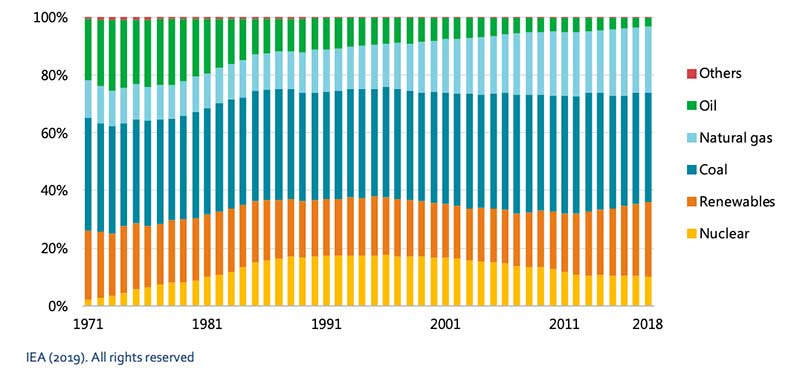

Already, the decline in nuclear power’s share in electricity generation has entirely offset the growth in the share of renewables since the late 1990s.

Check this out:

And for other low-carbon sources like wind and solar PV to fill the shortfall in nuclear, deployment would have to accelerate to an “unprecedented level”, says the IEA report.

“In the past 20 years, wind and solar PV capacity has increased by about 580GW gigawatts in advanced economies,” it says.

“But over the next 20 years, nearly five times that amount would be needed.”

Without policy changes, advanced economies could lose 25 per cent of their nuclear capacity by 2025 and as much as two-thirds of it by 2040.

Right now, there are now 54 reactors under construction – 59GW worth — of which 40 are in the developing economies, led by China, with 11 units, India (7), Russia (6) and the United Arab Emirates (4).

In advanced economies, Korea has the most units under construction (4), followed by Japan (2), the Slovak Republic (2), the United States (2), and Finland, France, Turkey and the UK (1 each).

READ: Uranium stocks guide — Here’s everything you need to know

But it’s not all dire news. The World Nuclear Association says over 100 power reactors with a total capacity of about 120GW are on order or planned, and over 300 more are proposed. Most reactors currently planned are in the Asian region, defined by fast-growing economies and the subsequent rapid rise in electricity demand.

“It is noteworthy that in the 1980s, 218 power reactors started up, an average of one every 17 days,” the association says.

“With China and India’s nuclear sectors growing, it is not hard to imagine a similar rate of reactor construction in the years ahead.”

For advanced economies, IEA exec director Dr Fatih Birol says policy makers that hold the key to the future of nuclear power. He proposes new market incentives and explicit government support for baseload nuclear energy.

“Electricity market design must value the environmental and energy security attributes of nuclear power and other clean energy sources,” he says.

“Governments should [also] recognise the cost-competitiveness of safely extending the lifetimes of existing nuclear plants.”