The Explorers: Spectrum Metals’ Paul Adams on dodging bullets and that 1 month, 525pc share price increase

Mining

Mining

The Explorers is Stockhead’s in-depth look at the people behind some of Australia’s most innovative and courageous junior mining companies. This week, resources reporter Reuben Adams chats with the managing director of Spectrum Metals (ASX:SPX), Paul Adams.

Spectrum Metals (ASX:SPX) was spinning its wheels in exploration purgatory as it pivoted from its previous incarnation as a rare earths explorer. It’s diminutive market cap over the past few years told the story.

But when Spectrum acquired a couple of historic high-grade gold mines late last year, everything changed.

One of these, Penny West, was one of the highest-grade open pit gold mines in Western Australian history, producing 85,000oz at a grade of 21.8 grams per tonne between 1991-1992.

Spectrum went into its maiden Penny West drill program on February 20 this year with a $5.3 million market cap.

It immediately struck bonanza grade gold about 150m north of the historic high-grade open pit, and by the end of March, Spectrum’s market cap was transformed; up over 500 per cent to $26.3 million.

Spectrum now believes it is onto a pretty amazing discovery at a project that has been sitting there, relatively unloved, for 30 years.

Managing director Paul Adams spent 20 years as a geologist and 12 years in equities research prior to accepting the top job at Spectrum in May last year.

He gives us some insight into what he calls ”a 7 week rollercoaster ride” and Spectrum’s high grade, brownfields project strategy.

“My background is 20 years in geology, management, and development for some pretty big mining companies, and this was an opportunity for me to get back to the coalface, as it were, and take on a project on my own.

“Originally, [Spectrum was looking to buy] an interesting gold asset in California, and I was brought in to conduct a technical vet on that project for the broker that I worked for at the time.

“It was a high grade, narrow vein gold project in northern California, with a mill and all the permits in place. On paper it looked like a pretty interesting little project — something that a small company like Spectrum could take on board.

“I expressed an interest and was offered an executive role at Spectrum, much to my surprise.

“We then entered into an option agreement with the vendors and were about to sign the second part of the option which would have committed us quite heavily.

“About four days before we were due to sign the documents a wildfire sprang up about 4km from the mine. The fire was blowing in the opposite direction of the mine, but I said ‘look guys, our intention is to go ahead, but I can’t sign anything if there’s a wildfire in the district’.

“The vendors were quite good about it and we agreed to take it day by day. We all thought that this fire would blow out in five days and we would go ahead and sign the option deal.

“But that didn’t happen, and the fire grew to catastrophic proportions; it ended up destroying 180,000 acres, 11,000 homes, and 6 lives were lost.

“Then the wind changed direction, and blew back towards the mine site. All the surface infrastructure at the mine – the mill, the offices, the gold room, the workshops, vehicles, trucks – got burnt to the ground.

“That probably would’ve been my first and last managing director role if I had said ‘let’s sign the document’ and the mine burnt down two weeks later. But still, we liked the strategy of finding small, rich, high grade gold deposits.

“Our view was to go for high grade so you can be robust through the metal cycle, because if you don’t have grade on your side things get very tough, very quickly.

“We don’t mind projects that look comparatively small. We aren’t drawn in to the old adage of ‘it’s got to be 100,000 ounces a year, over a 10-year mine life’.

“We are after projects that we can handle as small company; a project that can leverage off existing infrastructure, if possible – like existing open pits, declines, and previous drilling.

“Our chairman Alex Hewlett had coveted [Penny West] for about 18 months, but it was really a case of us being there at the right time with the right deal, and with the capacity to take it forward.

“The vendors were two private companies that had a done a pretty good job of drilling additional holes under the existing pit, but they needed funds to push the project forward.

“We happened to be there with the right deal. It was a scrip deal, which meant that they haven’t given up exposure to the project.

“It was a good deal for them, and a great deal for us. We put down $50,000 in cash and we gave them $950,000 in scrip — $1 million all up.”

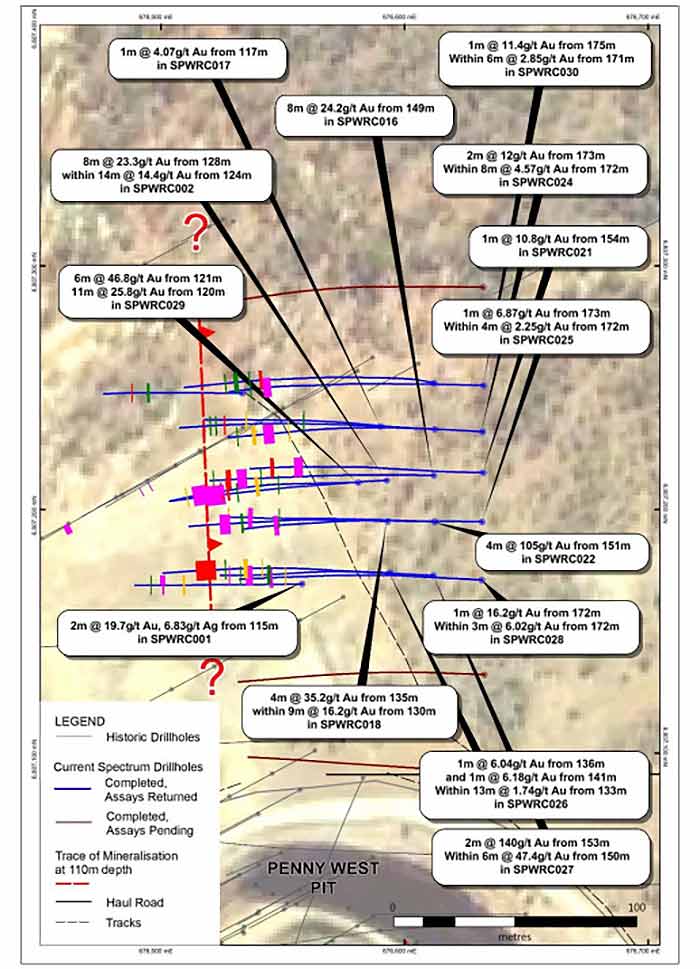

“Our initial focus was drilling underneath the open pit. But we had seen this isolated RC hole, about 100m north of the open pit, which had a 1m intersection at 6.5 grams per tonne.

“It was the only deep RC hole between the edge of the pit and a prospect called Columbia-Magenta, which is 2km north.

“It was only 1 metre, but we recognised that this intersection, which had never been followed up, might be the manifestation of an extension of the Penny West lode.

“So put three quick drillholes underneath to test that hypothesis. The first of those holes we delivered to the lab came back with 8m at 23 grams per tonne, within 14m at 14.4 gram per tonne.”

“I have no idea. I could be that the company ran out of money, the project could’ve been sold, or they may not have recognised the intersection for what it was.

“I mean, some of the intersections in the Penny West open pit were absolutely eyewatering. This open pit produced 1000oz per vertical metre, so 1m at 6.5g/t in comparison probably would’ve looked pretty rubbish.

“We had previously joked about finding another Penny West. We laughed about it, but it was also hard to believe that one of the highest-grade open pit mines ever mined in Western Australia had absolutely nothing around it for 25km.”

“And then as it turns out, hole 2 came out with this amazingly thick intersection at terrific grade.

“The geologist doing the logging told us ‘these look pretty good!’, so that afternoon we jumped into a car and drove 600km to site from Perth, picked up the bags, drove all the way back to Perth and put them in the lab. We did about 1400km in 20 hours.”

“And then of course, we completely changed our drilling program to concentrate on that one drill intersection. We wanted to make sure that it wasn’t a one hit wonder. We went back and tentatively put another two or three holes around it, in a fairly close pattern, so we didn’t miss anything.

“When it came back again with similar intersections we thought ’we are onto something here – this could be what we are looking for’.”

“With the results that we have got back so far, it appears that the structure is coherent. Some parts of it are thicker than others but it all looks to be the same thing.

“We’ve tested it now over a strike length of about 200m.

“We’ve got assays back in for about 100m, and we are waiting on the extension holes that we did to the south and north to tell us whether we’ve continued to hit the structure over that additional 100m.

“If we have hit that structure and it is mineralised, we will have about 200m strike length of that cohesive structure. The original Penny West deposit was also about 200m.”

“I would anticipate that we would get those assay results late April at this point. We want to see those before we can comment further.”

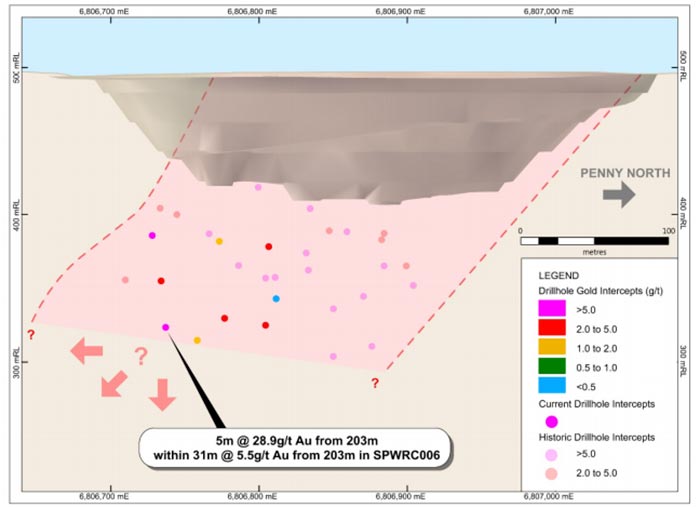

“We’ve still got some metres to drill underneath the pit, and we will be following up a very nice intersection that we got in our deepest, most southern hole at the bottom of the pit.

“We hit a high-grade intersection of 5m at 28.9g/t which, to be honest, was little bit of a surprise. We hadn’t really seen that before at Penny West at depth, so that’s interesting. If we can repeat that in another hole then I think there’s potentially the makings there of another chute.

“I’d like to think that by the end of the year we could have a maiden JORC resource and the opportunity to do some studies on how we would go about mining this thing. And if we keep having success then we’ll still be drilling.

“I’d love to be at a point at the end of the year where we are still drilling because we still haven’t found the edge. I know that’s a pipedream, but so was finding another Penny West.

“I wouldn’t put it past this project to yield more of its secrets.”