Sweating bullets about vanadium in 2019? Here’s what could happen

Mining

Mining

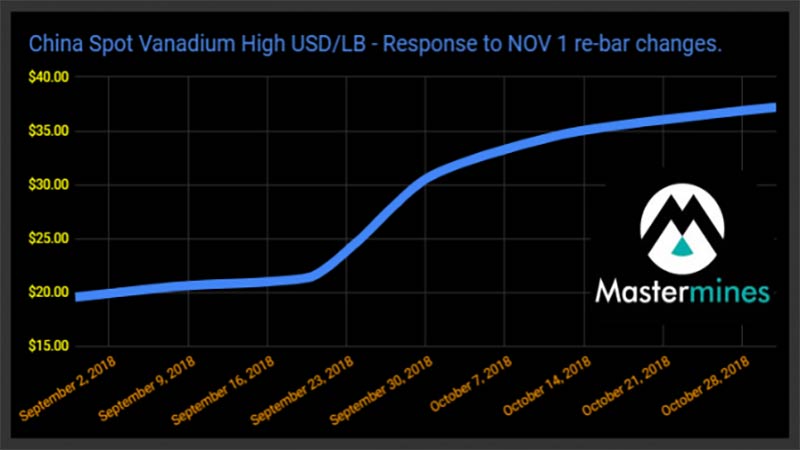

Vanadium was one of 2018’s standout performers, as spot prices surged from briefly above $US37 per pound — up from under $US5 in early 2017.

Vanadium pentoxide’s (V2O5) meteoric rise was attributed to a structural shortage of vanadium in the market – brought on by China’s stricter environment standards and its policy to double the vanadium used in rebar (a reinforcing steel used in concrete).

Steel uses 92 per cent of vanadium production. It takes only a small amount of vanadium to double the strength of steel and reduce its weight by 30 per cent.

David Gillam, boss of specialty consultancy Mastermines, says the late December price drop to $US20 a pound was bigger than expected – but could be generally attributed to seasonal factors.

The Chinese cut steel production substantially during the winter for environmental reasons.

“A lot of people don’t realise that steel production in China coming into winter is cut pretty dramatically to keep a lid on pollution,” Mr Gillam told Stockhead.

“This year we estimate between 30 and 35 per cent [of capacity will be cut], depending on the location of the steel mill.

> #China #Vanadium #spot prices continue falls

98% #V205 Flake USD 19.50/LB -32%

98% #V205 Powder USD 18.10/LB -25%#FeV50 also down 15%#NitroV down 24.5%#VRB becoming more viable on leasing.

Good news for V long term $12-$15/LB ideal LT

Expect prices to now begin to stabilize pic.twitter.com/tQ0j6upc7h— Mastermines (@VanadiumWorld) December 17, 2018

“We believe what caused this latest, fairly stark decline [in vanadium spot prices] is sellers not wanting to sit on what they had over that winter period — so they pushed it out into the market.

“We think the price may come back, maybe between the $US15/lb to $US20/lb mark [for V2O5 98% flake], but not too much further.”

Prices will bounce in early 2019

Mr Gillam says steel mills begin ramping up again sometime after Chinese New Year (Tuesday February 5), and he expects the vanadium price to strengthen in response.

Mastermines also believes that not all steel makers in China have complied with the new rebar standards yet – the catalyst for the most recent price surge.

“We aren’t sure that everyone has complied with those standards yet, or how much checking is going on to make sure [companies] are complying,” Mr Gillam says.

“So, it’s possible there’s going to be some more [upwards price] pressure to come from that.

“We find it hard to believe that everyone has complied on time.”

… but then prices must come down

It’s crucial that vanadium prices moderate to ensure the long-term sustainability of the industry, according to Mr Gilliam.

High prices were prompting some Chinese companies to substitute vanadium with cheaper alternatives like niobium or manganese where they could.

And despite what people are saying about the future of vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs) – at $US35/lb for vanadium they are off the table.

“They were not going to happen at those prices,” Mr Gillam says.

“We need to see vanadium selling at around $US10/lb for a straight sale VRFB to work — that’s the message we got in China.

“There’s a lot of contracts [for VRFB’s] that have been signed and are waiting on V2O5 to come down to a reasonable level.”

Low but not too low

Mastermines predicts a price of between $US10/lb and $US20/lb longer term – and they are hoping it will be towards the lower end of that range, although not too low.

Stone coal is an important vanadium-bearing resource in China – but the extraction process is dirty and environmentally damaging.

For this reason many mines have been closed down.

Mr Gillam says on average, these mine have an operating cost of between $US6/lb and $US8/lb – higher than the predicted operating costs of more advanced Australian explorers like Australian Vanadium (ASX:AVL) and Technology Metals (ASX:TMT).

The bar has been set by established global producer Largo, which has an operating cost of between $US4/lb and $US4.50/lb.

“The feeling in China is that about 30 per cent of stone coal could come back into the market, if they meet environmental standards,” he says.

“We would prefer to see as little as possible come back into the market.

“But at prices of between $US10/lb and $US12/lb these operators aren’t likely justify the additional investment required to meet new environmental standards.”

“And at between $US10/lb and $US12/lb both AVL and TMT would be quite viable.”

The Chinese are keen to lock in long term supply

There’s no doubt that the vanadium price increases seen over the past three months — and more importantly the effects of the new environmental policies — have scared a lot of the Chinese companies, Mr Gillam says.

They are very much now focussed on locking in long term supply.

“I have no doubt that a lot of this forward planning is happening in the vanadium space,” Mr Gillam says.

“Even from the steel and alloy guys — they would be well aware that vanadium flow batteries are a risk to their supply.”

But again, this surge in demand from battery makers is reliant on a more acceptable vanadium price.

“This is the point I keep making to shareholders,” Mr Gillam says.

“It’s not beneficial for vanadium to price itself out of the market.

What we want is stability at a reasonable price for end users, so that these developing markets continue to grow.”

Vanadium battery tech is evolving fast

Despite high vanadium prices, none of the battery companies had simply stopped – they were focused on refining and improving.

Some of them were even looking at vanadium-lithium hybrid systems.

“Our opinion is that hybrid systems are the future for VRBs,” Mr Gillam says.

In November, UK company redT installed a 1MWh vanadium flow / lithium-ion hybrid energy storage system in Melbourne’s Monash University.

The system comprised 900kWh of vanadium flow machine technology, coupled with a 120kW lithium battery.

RedT says a “hybrid system combines the best of both technologies to serve complex energy needs”.

The two together is great solution, Mr Gillam says.

Mastermines is also aware of four Chinese institutes or universities working on using vanadium in electric vehicle (or EV) battery packs.

Vanadium has its advantages, Mr Gillam says.

It can fast charge very easily because it doesn’t heat up the way a lithium-ion battery does.

It is also almost unaffected by cold climates, whereas a lot of lithium batteries in EV’s can lose up to 25 per cent of their range.

This has become a bit of a problem in some cold climates, like Northern China – where range figures quoted by some EV manufacturers were not relevant.

There’s one in particular that Mastermines can’t talk about yet that Mr Gillam calls “extremely interesting”.

“We believe its moving forward as well,” he says.

“We heard it’s going to pre-production testing, which means things have gotten far more serious.

I’m not saying vanadium is going to happen for EVs, but it is certainly being tested.”

ASX Vanadium Stocks: Here’s Everything You Need to Know>>>

Next year is probably going to be a bumpy one for resources stocks.

“I feel we are bouncing around the bottom [of the cycle], but your guess is as good as mine,” Mr Gillam says.

“We look at cycles for the market overall, we look at cycles for metals and minerals, and we look at cycles for companies.

“It doesn’t really matter where you look at the moment — all those cycles are at a low spot.”

And the added danger for advanced vanadium explorers is that cashed up miners or end users may try and buy them on the cheap, Mr Gillam says.

“I look at some of the market caps for some pretty amazing resources worldwide, and those market caps look pretty low,” he says.