Expert view: where vanadium is going and how to choose the right stocks

Mining

Mining

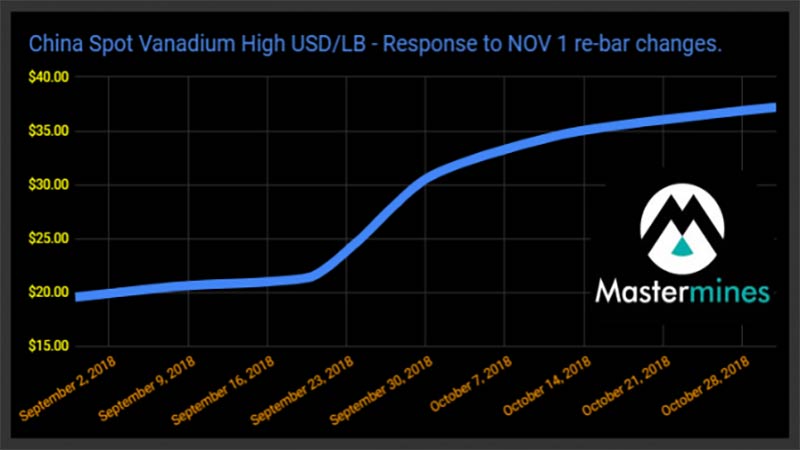

Vanadium is one of the year’s best performing metals measured by its spot price, which has risen above $US37 per pound — up from $US5 in early 2017.

However spot prices — the price of a commodity ready for immediate delivery — shouldn’t be relied on too heavily compared to longer term pricing says David Gillam of mining industry consultancy Mastermines.

Mastermines is a specialist company that has strong ties to China and helps Australian miners with marketing and securing sales deals.

Miners and their customers typically prefer longer term pricing agreements to ensure security of demand and supply.

“We tend to think of spot pricing as a market indicator – [albeit] a very important market indicator,” Mr Gillam says.

“The actual spot price is not really indicative of what a miner would get in a long-term contract.”

Either way, while the spot price is “a little too high at the moment” to be sustainable, general vanadium prices will remain elevated well above ‘pre-boom’ levels, Mr Gillam says.

“It’s not going to keep going up like this. You can see that it has almost doubled in two months,” he says.

“There is going to be a levelling off point, and there’s going to be a back-off point.”

Where it levels off to will give the market some indication of what to expect for the next two or three years, Mr Gillam says.

Mastermines expects spot prices will stabilise at about $US30/lb in the short term – far healthier than the $US4 to $US6 range it bounced between from 2009 to early 2017.

Vanadium’s popularity has prompted a flood of small cap ASX-listers to jump into the space.

But how can retail investors cut through the hype to choose a winner?

Mastermines believes only about 10 per cent of vanadium projects are good enough to become long term prospects.

“We are looking for someone that can be the next [major vanadium producer] Bushveld or the next Largo,” Mr Gillam says.

“This means ore grades of around 0.8 per cent to 1.2 per cent for starters.”

But most importantly a project needs operating costs of about $US4/lb of vanadium produced.

“That’s really critical because we know the Chinese – who want prices to drop – want to align themselves with companies that can produce around that Largo [ a major producer of vanadium] price of around $US4/lb,” Mr Gillam says.

“They want to know that you are still going to be producing if the price does fall that severely.

“There is only handful of companies that are there with a shot, in our opinion.”

The other big question for investors is whether the vanadium price increases are sustainable.

History shows us that vanadium prices are incredibly volatile, with pattern of long periods of low prices followed by a spike, then a fall.

In the first half of 2005 a spike in vanadium prices to over $35/lb — and subsequent drop — happened with such velocity that previous spikes seemed insignificant in comparison.

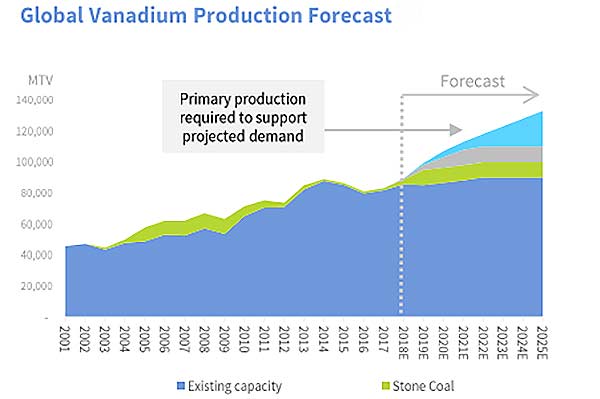

The consensus from miners and analysts is that it is different this time, because there’s a gap between supply and demand that will not be filled until new mines come online.

For starters, China’s own vanadium production has declined because of tougher environmental standards led to a number of mines shutting down.

The import of many vanadium-bearing slags was also banned as part of the war against pollution.

So the chances of supply coming back online to flood the market and drop the vanadium price are very low.

The only significant near term supply increases are from established South African miner Bushveld (LON:BMN) and Brazil based Largo (TSX:LGO). But that isn’t enough, Mr Gillam says.

Current vanadium demand is about 100,000 tonnes per annum, but that is now tipped to triple over the next five to six years.

“A couple of years ago, the Largo chief executive was saying that we need a Largo [equivalent production] every year to cope with demand,” Mr Gillam says.

“I don’t think that is far off the truth.”

In November, China introduced stricter standards to double the amount of vanadium used in its rebar — a reinforcing steel used in concrete.

92 per cent of vanadium is already used in steel. It takes only a small amount of vanadium to double the strength of steel and reduce its weight by 30 per cent.

And there is very little chance of the Chinese relaxing these new environmental and rebar standards, even if vanadium prices remained high, Mr Gillam says.

“In the past environmental standards were handled by the Chinese provinces, with direction from the central government,” he says.

“But our understanding now is that the central government is sending teams into the provinces directly.

“They are showing every indication that the [new standards] are here to stay.”

#Vanadium could have its “Elon Musk moment” as it advances towards powering 25 per cent of stationary battery storage by 2028, says #batterymetals expert @sdmoores of @benchmarkmin. #ASX https://t.co/JxZWaihBct

— Stockhead (@StockheadAU) September 18, 2018

But the beauty of vanadium is that there is no other mineral like it, Mr Gillam says.

“It has this balancing act going — if the price drops, we get flow batteries kicking in a big way,” he says.

Because flow batteries become far more economical, it increases vanadium demand once again,” he says.

“It’s like a set of scales, and I think the vanadium price is protected for quite a number of years to come.”