EVs, asteroids and automation – 6 mining trends that are set to sort the winners from the losers

Mining

Mining

Automation, climate change, geopolitical risk, and a scarcity of ‘easy’ mineral deposits – these are just a few things that miners and explorers are contending with right now.

Nicolas Maennling and Perrine Toledano from the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment believe these trends, and how miners react to them, will determine which companies succeed and fail in the future.

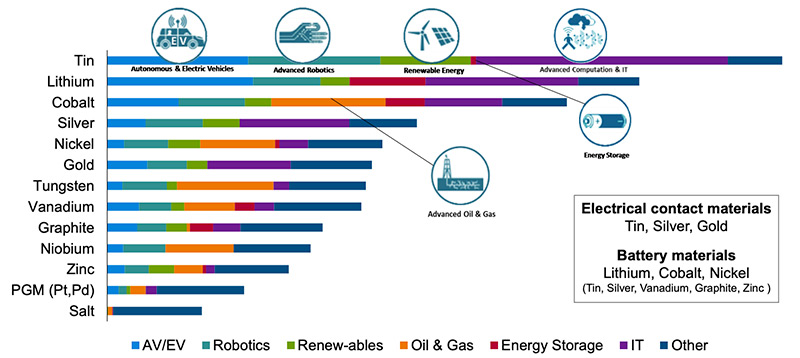

Wind, solar, storage batteries and electric vehicles are more mineral-intensive than their fossil fuel-based counterparts, experts say.

Which is great — but this transition also means miners will need to reduce their own emissions.

“Companies that power their operations with renewable energy, operate electric or hydrogen-powered truck fleets and integrate recycling in their value chains will be best placed to sell low-carbon premium minerals,” say Maennling and Toledano.

Companies will need to dig deeper and venture into frontier mining areas as world-class mineral resources in low-risk areas are exhausted.

“Mining jurisdictions with higher perceived risks may see increasing levels of interest from investors,” say Maennling and Toledano.

New technologies for exploration, extraction and processing could also make previously uneconomic projects viable.

And in the search for high-grade ore deposits, deep sea and asteroid mining will be increasingly explored by governments and companies.

China sparked a massive commodity boom between about 2000 to 2014 – but then prices collapsed, many miners went to the wall, and people lost a lot of money.

So investors like the big banks are becoming more selective, with commodity and jurisdiction (is the project in a risky country?) playing a key role in their decision-making.

To spread the risk of developing a new project – especially for a small cap — more unconventional financing solutions are becoming popular.

These include things like royalty agreements, which give investors a share in future revenue; and streaming deals, which means investors pays money now for a percentage of the company’s future production.

READ: Here’s how lenders decide which mines are worth risking billions on

Miners love to talk about how they are part of the community where they operate – but the fact is, obtaining a social license to operate has been a challenge in recent years.

Many proposed projects are rejected, and operations are disrupted by protests, say Maennling and Toledano.

“Local opposition to mining is likely to increase if no new business models are developed that benefit the affected communities,” they say.

This includes effectively tackling mine rehabilitation, providing real employment opportunities, and taking innovative approaches to minimising water use and emissions.

What data should be shared by miners continues to be a major area of debate, the report says.

Governments, for example, could push for disclosure of subsidiary structures to address tax evasion, or consumers will seek to increase value chain transparency.

“It will be key for companies to work together with other stakeholders in order to understand the types of data that should be made available and the appropriate format that data disclosure should take, in order to ensure standardization, usefulness and impact,” say Maennling and Toledano.

Policymakers are increasingly enacting local laws and regulations which require minerals to be processed before they are exported.

For example the Democratic Republic of Congo has labelled cobalt a “strategic” metal and slapped a 10 per cent royalty on it. It’s also threatening to re-enact a ban on all cobalt and copper concentrates.

Indonesia did the same thing with unprocessed nickel exports between 2014 and 2017 to incentivise local smelting.

“Further consolidation, geopolitical manoeuvring and muscle-flexing could create challenges for companies that have so far prospered under a system of relatively free trade – while creating opportunities for domestic projects that might not be economically viable without government intervention,” the report says.